Aulacaspsis yasumatsui

The scales of mature A. yasumatsui females are white, 1.2 to1.6 mm long and highly variable in form. They tend to be pear-shaped but are often irregularly shaped, conforming to leaf veins, adjacent scales, and other objects. The scale of the male is 0.5 to 0.6 mm long, white, and elongate.

Cycas reveluta and C. taitungensis are their favored host plants. They are Widely distributed world wide.

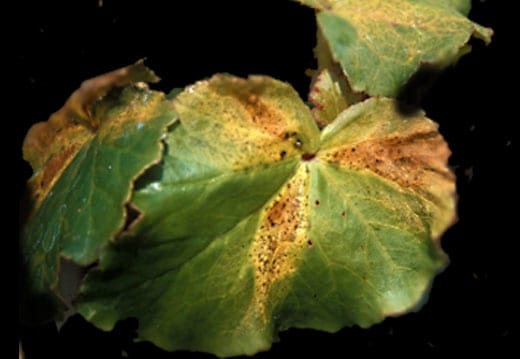

The unusually dense populations and rapid spread of Asian cycad scale suggests it is an exotic invasive and has few, if any natural enemies. If left untreated, this pest will kill its plant host. At its worst, an infestation of the Asian cycad scale can completely coat a medium-sized sago within several months. The coating can be composed of several layers and include a high proportion of dead insects as well as live scale insects. Heavy infestations can include up to 3000 scales per square inch in several layers.

The Asian cycad scale is unusual in that it can also infest the roots of cycads. These scales have been observed at depths up to 24 inches.

They can cover the leaves of Cycads as to look like snow.

In general, scale insects hatch into a “crawler” stage capable of movement, or in some species, even limited flight. When they find a suitable spot on a plant, they insert their mouthparts, called a stylet (much like a straw), into the plant and start feeding. Shortly afterwards they begin to create a covering over themselves. They will stay this way until they die.

Females go through three instars, and the average time from egg hatch to adult is 28 days. Females can lay more than 100 eggs which hatch in eight to 12 days at 25 degrees C. Most females do no live longer than 75 days.

Only a few other species of armored scale insects infest roots and those roots are generally located near the soil surface.