The pine Tent Caterpiller (Thaumetopoea pityocampa)

A moth of the family Thaumetopoeidae. Sometimes placed in the genus Traumatocampa, it is one of the most destructive species to pines and cedars in Central Asia, North Africa and the countries of southern Europe.

The urticating hairs of the caterpillar larvae cause harmful reactions in humans and other mammals. The species is notable for the behaviour of its caterpillars, which overwinter in tent-like nests high in pine trees, and which proceed through the woods in nose-to-tail columns, protected by their severely irritating hairs as described by the French entomologist Jean-Henri Fabre.

LIFE CYCLE:

Though most pine processionary moths only live one year, some in high altitudes or more northern areas may survive for over two years. The adult moths lay their eggs near the tops of pine trees. After hatching, the larva eat pine needles while progressing through five stages of development. In order to maintain beneficial living conditions, silken nests are built over the winter. Around the beginning of April, the caterpillars leave the nests in the procession for which the species is known. They burrow underground and emerge at the end of summer.[3] High numbers of adults are produced in years with a warm spring.

The eggs are laid in cylindrical bodies ranging from 4 cm to 5 cm in length. The eggs are covered with scales which come from the female and mimic pine shoots.[3]

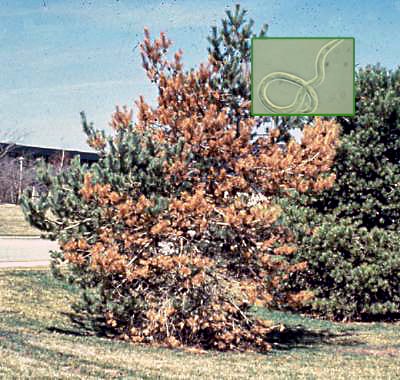

The larva is a major forest pest, living communally in large “tents”, usually in pine trees but occasionally in cedar or larch, marching out at night in single file (hence the common name) to feed on the needles. There are often several such tents in a single tree. When they are ready to pupate, the larvae march in their usual fashion to the ground, where they disperse to pupate singly on or just below the surface.

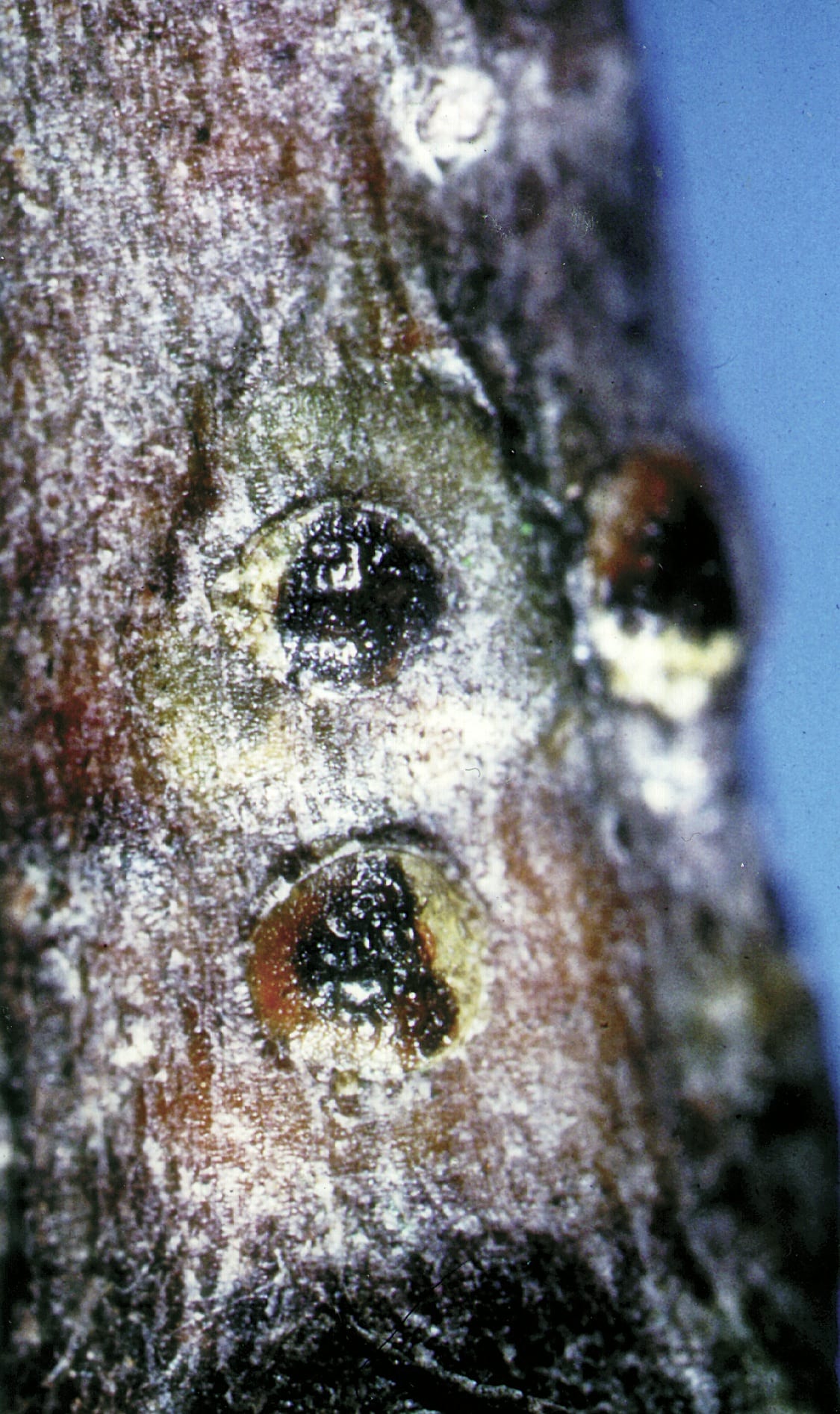

The moth’s pupal stage occurs in a white silken cocoon under soil. The pupae measure around 20 mm and are a pale brownish-yellow color that changes into a dark reddish brown.

As an adult, T. pityocampa has predominately light brown forewings with brown markings. The moth’s hind-wings are white. Females have larger wingspans of 36 to 49 mm, compared to a male’s 31 to 39 mm.[3] Adults only live for a single day, when they mate and lay eggs. How far they are able to spread depends on how far the female is able to fly during her short time as an adult. Her average flying distance is 1.7 km, with a maximum recorded of 10.5 km. The species flies from May to July